In most situations, children’s education is negatively affected by internal displacement, with school attendance often halted temporarily or for good. But one of the most exciting – and important – things about data is that sometimes the results of analysis surprises us with unexpected findings.

This was the case when the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) undertook a study in Somalia in 2019 to measure the consequences of internal displacement on children’s education, as part of our research on the socio-economic impacts of internal displacement.

The study produced new data which suggested that some children who had been internally displaced in Somalia had higher school attendance rates in their new host areas than in their home areas.

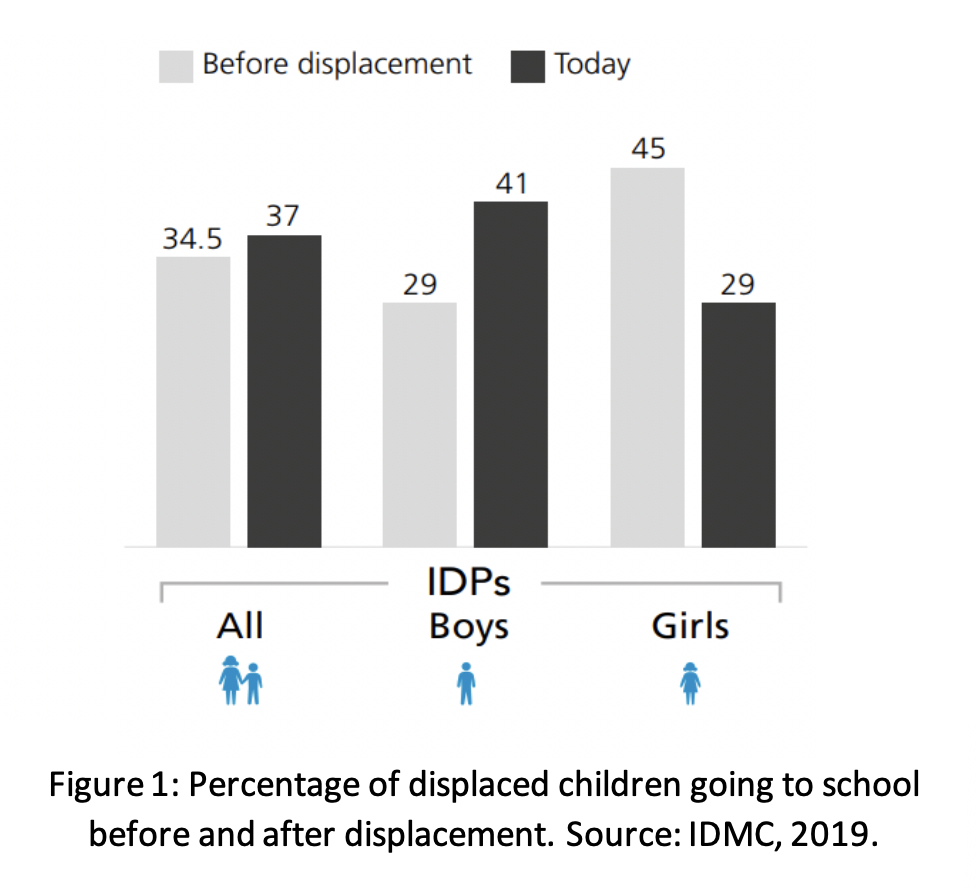

IDMC surveyed internally displaced people (IDPs) who had left their rural homes in 2017 or 2018 for the capital city of Mogadishu after drought wiped out their cattle and their livelihoods. According to interviews with parents, more displaced children were going to school after displacement than before – 37 percent of sampled children were attending school, compared to 34.5 percent in their area of origin – likely due to greater access to schools in urban areas.

But when we looked beyond average attendance rates and disaggregated the data by sex, we uncovered more surprises.

The data showed that more boys were going to school after displacement, but far fewer girls were going to school (Figure 1). More research is needed to unpack these findings further, but this is likely the result of two main factors:

- Boys who had to care for cattle in their home area were now able to go to school instead.

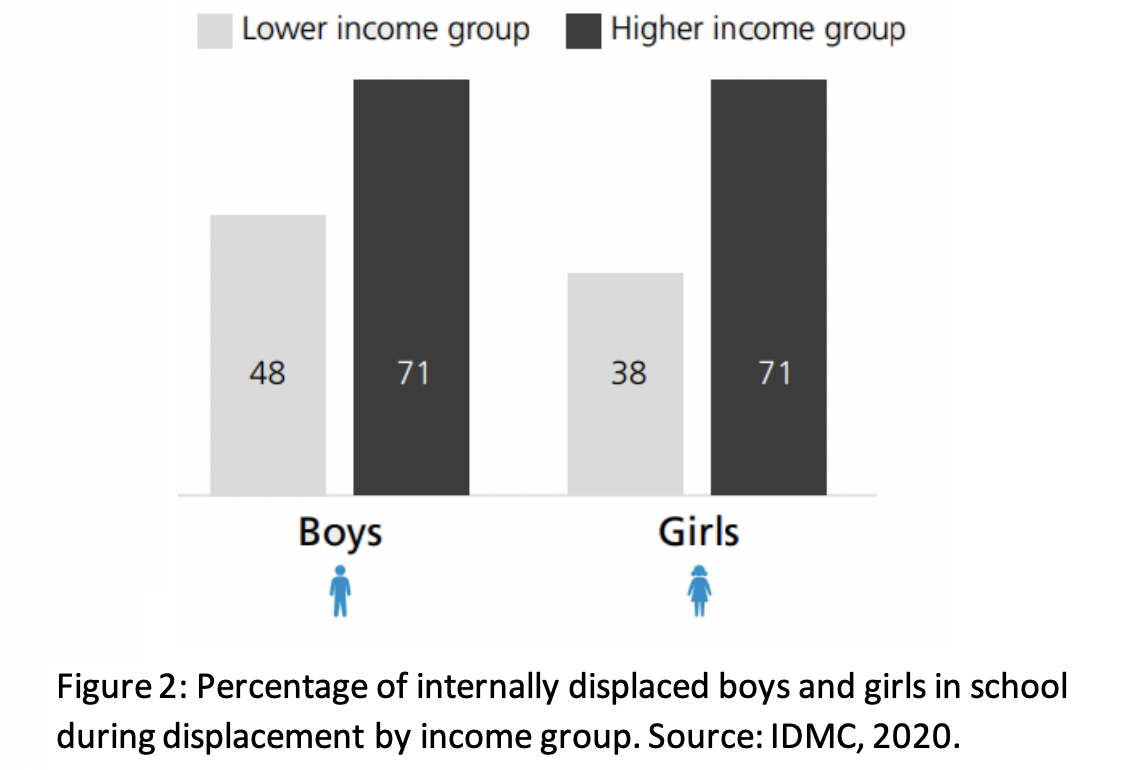

- However, many families suffered from increased financial difficulties. If they could only afford to send some of their children to school, they would send their sons rather than daughters. This is confirmed by the fact that families from higher income groups sent their daughters to school at equal rates as their sons, while lower income groups sent 48 percent of their sons and 38 percent of their daughters (Figure 2).

By looking beyond an average and disaggregating data, we uncovered disparities that are critical to informing the provision of tailored financial or educational support to families from lower income groups with several children, including daughters.

This example confirms three priorities for research on internal displacement:

- Case-specific data collection is essential. Displacement situations vary. Blanket approaches based on averages, or findings from other situations, are not enough to ensure that IDPs’ unique and specific needs are met.

- Disaggregation by sex and age is needed to capture inequalities in impacts and access to resources. In this case, had the data not been disaggregated by sex, girls’ disadvantage would have been unknown, hidden in the data. Aid providers then could have assumed that all children were going to school more after displacement.

- Gender-specific analysis is required. Sex-disaggregated data needs to be complemented with more in-depth gender analysis to understand the context in order to make valid policy recommendations that support people affected by internal displacement.

These priorities are at the heart of the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre’s Inclusive Data Charter action plan. In October 2018, IDMC became a champion of the Inclusive Data Charter (IDC), joining a cohort of other organizations committing to improve the quality, quantity, financing, and availability of inclusive and disaggregated data.

For the first 20 years of its existence, IDMC identified, verified, and analyzed data collected by other organizations in countries affected by internal displacement, producing bi-annual estimates of the number of people internally displaced by conflicts and violence around the world, and of the number of new displacements linked with conflict, violence, or disasters.

But much remained unknown: how many people lived in internal displacement because of disasters or climate change? How many were men, women, children, or older people? What were their specific needs?

Signing up to the IDC and going through the process to develop an IDC action plan motivated us to take stock of what data was available to answer these questions. IDMC undertook an internal review of key data gaps and challenges, which helped frame the focus of our inclusive data action plan. We decided to prioritize the need for primary data collection and its disaggregation and analysis by age, sex, and other characteristics.

IDMC developed original data collection tools to start bridging knowledge gaps around the impacts of internal displacement, displacement in the context of climate change or slow-onset disasters, and the links between cross-border and internal displacement. In the first year of IDMC’s engagement with the IDC, 2,800 quantitative surveys were conducted in 15 countries, including the Somalia case study. All were disaggregated by sex and age.

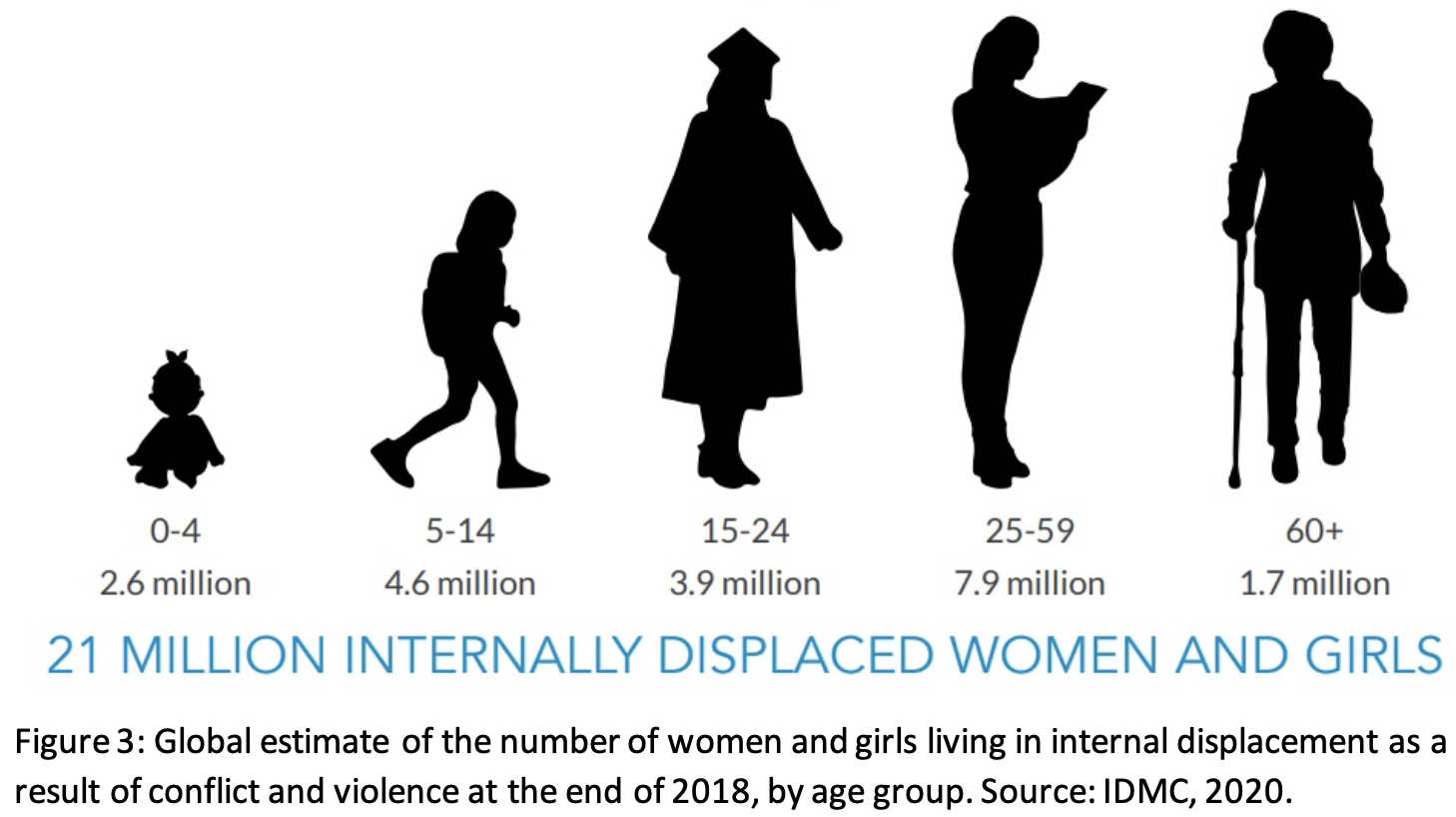

This new data, added to the sex and age-focused analysis of existing datasets, led to the publication of the first-ever estimates of the number of internally displaced children and women in 50 countries and at the regional and global levels. Figures were also broken down by broad age groups (Figure 3). We arrived at striking findings: 17 million children and 21 million women and girls are living in internal displacement because of conflict and violence around the world. These estimates highlight the need to dedicate specific plans and responses to meet their needs. The figures produced by our research were used and referenced by high-level actors, including UNICEF, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights of IDPs, and UNHCR.

By sharing these reports, insights, and emerging best practices from our dedicated research programme on differentiated impacts of internal displacement with the IDC network, we generated interest from other IDC champions and triggered new partnerships, including with the Consortium for Street Children and UNFPA. Both will contribute their data and expertise to an upcoming joint publication on internally displaced youth.

IDC has been a catalyst for IDMC’s work to advance inclusive and disaggregated data on internally displaced people. Joining the IDC encouraged IDMC to take stock of data gaps in order to provide an inclusive, more precise and comprehensive picture of internal displacement, and inspired us to focus our approaches and resources to bridging the gaps identified. IDMC has connected with new partners to exchange data and expertise with, and with whom we can disseminate key figures, messages, and recommendations further. As a result of this momentum and rapid progress in the first year of being a champion, internally displaced women, men, girls and boys now have more visibility. Their unique needs can be advocated for and hopefully, fulfilled by development partners and policymakers.